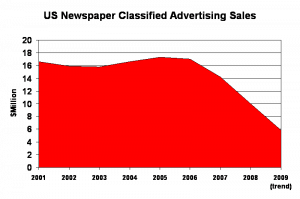

The Newspaper Association of America made no attempt to draw attention to its release of the first quarter financial results for America’s newspapers — and with good reason. Sales skidded an unprecedented 29.4%, driven by disasterous results in classified advertising amid the weakest economy in 60 years. Alan Mutter notes that if this trend continues, the US newspaper industry could close out 2009 with total sales of less than $30 billion — a 40% drop in just four years.

The Newspaper Association of America made no attempt to draw attention to its release of the first quarter financial results for America’s newspapers — and with good reason. Sales skidded an unprecedented 29.4%, driven by disasterous results in classified advertising amid the weakest economy in 60 years. Alan Mutter notes that if this trend continues, the US newspaper industry could close out 2009 with total sales of less than $30 billion — a 40% drop in just four years.

The wreckage is across the board — even online sales were off more than 13% — but the worst-hit sectors were cyclical ones: Employment classified advertising down 67.4%; Real estate classifieds off 45.6% and automotive classifieds down 43.4%. All in all, classified ad sales were down 42.3% for the quarter. “In records published by the NAA that date to 1950, there is no precedent for the sort of decline suffered in the first three months of this year,” Mutter writes.

Slate’s Jack Shafer has a historical review of the factors that got the newspaper industry into this fix. Publishers knew by the 1970s that they were toast, he says. Demographic factors were to blame. The flight of professionals out of the cities and into the suburbs challenge the economic model of the big dailies, and their halfhearted attempts to regain momentum mostly failed. Some executives took consolation in the fact that their circulation was growing despite the reality that the gains badly lack lagged overall population growth. The game was really over long before the story began to show up in the financial results.

More Fodder for Pay-Wall Debate

In the continuing debate over whether newspapers should charge for content, Martin Langeveld contributes perspective from Albert Sun, a University of Pennsylvania math and economics student with an interest in journalism.

Speaking at a recent conference put on by the Donald W. Reynolds Journalism Institute at the Missouri School of Journalism, Sun suggested that newspapers shouldn’t be too monolithic in their approach to pricing. Rather, they should take inspiration from the airline industry, which charges different prices for the same seats depending on traveler needs.

In the same manner, newspapers should look at their product as a collection of boutique services, each with different price tiers depending upon perceived value. For example, a casual reader may pay nothing for a weather forecast, but a weather bug might part with $10 a month for detailed technical reports and historical records. Langeveld writes:

Establishing a single price point for online content…might work for a time but is not revenue-maximizing in the long run. The right way entails the exploitation of a variety of niches all along the curve – and therein lies the problem, since the culture of newspapers is still mainly that of a monolithic, one-size-fits-all daily product, whether in print or online.

In another post, Langeveld flags a quote from Denver Post publisher and MediaNews Group CEO Dean Singleton in an interview with the Colorado Statesman:

We will be moving away from giving away most of our content online. We will be redoing our online to appeal certainly to a younger audience than the print does, but we’ll have less and less newspaper-generated content and more and more information listings and user-generated content.

Devalued Journalists Fight Back

Two stories caught our eye this week about journalists attempting to skewer the current trend toward devaluing their profession.

Two stories caught our eye this week about journalists attempting to skewer the current trend toward devaluing their profession.

Three Connecticut alternative publications – the Hartford Advocate, New Haven Advocate and Fairfield County Weekly – outsourced all of the editorial content for last week’s issue to freelance journalists in India. But instead of burying the move, the papers actively promoted debate with a provocative headline: “Sorry, we’ve Been Outsourced. This Issue Made In India.” And to drive home the absurdity of the whole affair, the editors assigned Indian journalists to principally cover local news, entertainment and culture.

The move had elements of a publicity stunt playing off of American capitalism’s current love affair with all things Indian. However, editors made a sincere effort to see the project through, producing nine stories about local affairs written by reporters half a world away. They wrote about their experience:

If our owners want to replace us with Indians, all we can say is good luck! If they find locating, hiring and keeping after these writers half the challenge we did, they might think twice about replacing us. Far from giving us a week off, it took practically the entire editorial staff to assign, edit, manage and assemble this project.

The myth that Indian reporters work for peanuts was belied by one Indian veteran who asked for $1 a word, which is less than what the publishers pay in the US. The experiment also had its lighthearted moments such as when one overseas journalist shared a vindaloo recipe with the publicist for a mind-reading act.

Michelle Rafter writes about the questionable editorial oversight practices at content aggregators. These Web-based organizations, which principally republish material from contributors in exchange for a share of the revenue, have been labeled in some quarters as the future of journalism. If so, then the experience of Los Angeles freelancer L. J. Williamson indicates that they have a long way to go.

Williamson wrote a series of articles for Examiner.com, a string of localized aggregation sites targeting major cities. She noticed that her stories were passing through to the site with little or no editing. Editors seemed far more interested in traffic-driving strategies. So Williamson began concocting increasingly outrageous topics full of “exaggerations and half-truths. I also wrote a series of preposterous articles on topics like why peanuts should be banned, why panic was a totally appropriate response to the swine flu outbreak, and why schoolchildren were likely to die if they were allowed to play dangerous games such as tag,” she wrote in an e-mail to Mediabistro.com’s Daily FishbowlLA. “And no one at Examiner noticed or cared what I said or did for quite some time.”

Williamson was finally outed by lawyers for one party that was victimized by her reports. She was “fired” from a job that had never paid her and had to settle for the satisfaction of telling her story to the world.

Miscellany

The Wall Street Journal says a private equity firm, HM Capital, is close to a deal to acquire Blethen Maine Newspapers, which owns the Portland Press Herald/Maine Sunday Telegram, and two smaller newspapers. The small chain has been on the block for more than a year, during which time it has become an albatross around the neck of the Seattle Times, which owns Blethen.

The Nieman Foundation has suspended its annual conference on narrative journalism, dealing another blow to the already dwindling support for long-form storytelling.

The long-form clearly isn’t dead at Denver-based 5280 magazine. It has an Investigation Of The Circumstances Leading Up To The Closure Of The Rocky Mountain News that runs to nearly 10,000 words. We haven’t had a chance to read it yet, but feel free to knock yourself out and send us a summary.

Writing on True/Slant, Ethan Porter says Matt Drudge’s popularity is waning. A Drudge Report story last week about a potentially incendiary quote from House Speaker Nancy Pelosi went nowhere, he says. Could Drudge’s conservative politics be losing favor in a recession wracked world? Dare we be so hopeful?

McClatchy Watch catches the Miami Herald in the act of promoting circulation with an offer of a free subscription to a magazine that hasn’t been published in two years.

There’s plenty of buzz in the blogosphere about an

There’s plenty of buzz in the blogosphere about an