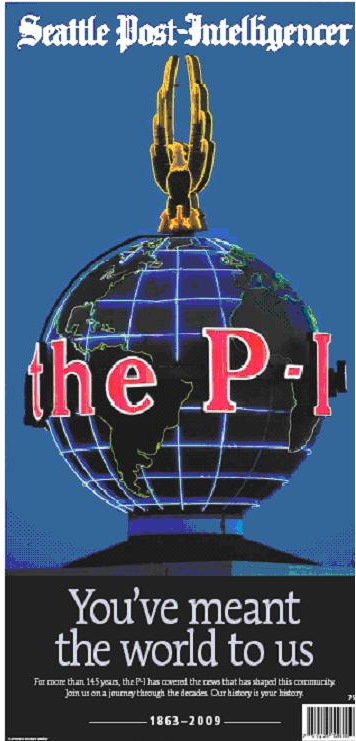

The week started depressingly with the demise of the Seattle Post-Intelligencer and then brightened with the emergence of a rescue plan for the San Diego Union-Tribune. We’d like to close it out with an inspiring view of the future by Steven Berlin Johnson, founder of the hyperlocal community site, outside.in.

Speaking at the South by Southwest conference last week, Johnson delivered one of the most cogent and optimistic perspectives on the future of journalism that we’ve ever read. His essay builds upon Clay Shirky’s excellent discussion last week of why revolutions are messy but necessary. Johnson does it by pointing to two of the most mature information ecosystems of the online world – technology and politics – and contrasting the state of media today to that of 20 years ago.

Speaking at the South by Southwest conference last week, Johnson delivered one of the most cogent and optimistic perspectives on the future of journalism that we’ve ever read. His essay builds upon Clay Shirky’s excellent discussion last week of why revolutions are messy but necessary. Johnson does it by pointing to two of the most mature information ecosystems of the online world – technology and politics – and contrasting the state of media today to that of 20 years ago.

There is no comparison. As an Apple Mac fan from the early days, Johnson used to wait at the local newsstand for each issue of Macworld magazine to arrive. In the late 1980s, “It might have taken months for details from a John Sculley keynote to make to the College Hill Bookstore; now the lag is seconds, with dozens of people liveblogging every passing phrase from a Jobs speech. There are 8,000-word dissections of each new release of OS X at Ars Technica, written with attention to detail and technical sophistication that far exceeds anything a traditional newspaper would ever attempt.” Even Macworld, which used to dispense news only once a month, “published twenty-six different articles on Apple-related topics yesterday.”

24X7 Politics

The political sphere is also booming with information. Barack Obama’s controversial race speech in Philadelphia was seen in its entirety by 8 million people online. In 1992, “It would have been reduced to a minute-long soundbite on the evening news. CNN probably would have aired it live, which might have meant that 500,000 people caught it.” Not only was the entire presidential campaign live-blogged, but it was covered by a swarm of interested Web publishers who dissected every event and issue. And by the way, Web users all had access to a bounty of information directly from both candidates. Two decades ago, such details were hard to get and they were mostly summarized and passed through the filter of the local newspaper.

Johnson asserts that the transformation that has already taken place in technology and political news will spread into other domains as well. While praising The New York Times, he notes that a big paper can’t be all things to all people. “Every week in my [Brooklyn] neighborhood there are easily twenty stories that I would be interested in reading: a mugging three blocks from my house; a new deli opening; a house sale; the baseball team at my kid’s school winning a big game. The New York Times can’t cover those things in a print paper not because of some journalistic failing on their part, but rather because the economics are all wrong.”

Johnson says he gets that local news from blogs like Brownstoner, which is one of nearly 2,000 blogs focused on Brooklyn.

Future in Aggregation

Is there a future for professional news organizations in all this? Absolutely, Johnson asserts. “If they embrace this role as an authoritative guide to the entire ecosystem of news, if they stop paying for content that the web is already generating on its own, I suspect in the long run they will be as sustainable and as vital as they have ever been. The implied motto of every paper in the country should be: all the news that’s fit to link.” And this will open the door for new organizations to step in with the international coverage that is unquestionably threatened as traditional newspapers decline.

Johnson’s use of the mature new-media markets of technology and politics is an innovative approach to envisioning a future for professional news gathering, one in which aggregation and interpretation trump original reporting. With millions of enthusiasts now providing front-lines coverage, the new role of professional journalists will be to organize and make sense of it all. This doesn’t make them any less important than they are today. They’ll just deliver a different kind of value.

Layoff Log

In the meantime, though, the transformation takes its toll:

- The Minneapolis Star Tribune, already languishing in bankruptcy, is laboriously negotiation cost cuts with its unions in an effort to save $20 million in annual expenses. Its 116-employee pressmen’s union just approved contract revisions that will result in wage reductions, 24 layoffs and reduced staffing on the presses. Next up are negotiations with delivery and newsroom unions.

- The Memphis Commercial Appeal is cutting 19 newsroom jobs. No word on whether additional reductions are hitting other departments.

- McClatchy papers continue to cut jobs, working toward a corporate goal of 1,600 reductions, but McClatchy Watch says it isn’t going to happen. “Unless it plans to shut down a couple of its papers, McClatchy will not come anywhere near laying off 1,600 employees,” the site says, and it has title-by-title numbers to prove it. However, commenters don’t entirely agree. A lively debate over the blog’s estimates ensues, along with a side argument over stylistic issues, which seems to crop up frequently when journalists disagree. Meanwhile, the site reports on recent layoffs: 47 in Anchorage, 20 in Columbus, 14 in Lexington and 10 in Modesto. The Idaho Statesman is also laying off 25 people and imposing salary cuts.

- Three staffers are gone at the Las Cruces Sun-News. One of them is “the typist who transcribes calls to Sound Off!” We hope that’s not a full-time job.

- Morris Communications has managed to avoid layoffs so far, but it’s is cutting staff salaries 5% to 10% at all its properties, including the Amarillo Globe-News.

And Finally…

In times of trouble, people now have a new way to commiserate and cooperate: Facebook. A new group called Newspaper Escape Plan has been hatched to enable laid-off journalists to pull together and share job-hunting tips and gossip about the business. You can go there to learn about services like Publish2, which is a social bookmarking service for journalists. Follow it on Twitter.

The AP posted this sobering photo of discarded newspaper racks languishing in a San Francisco junkyard.