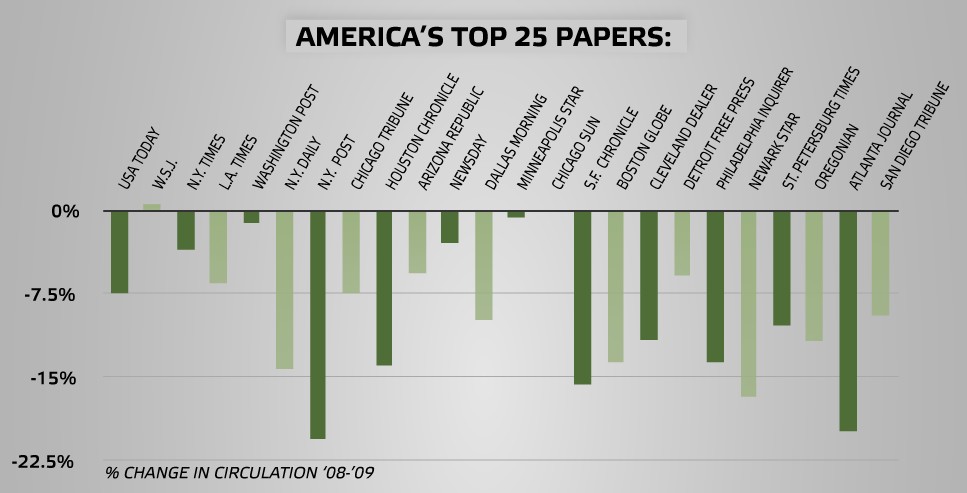

Implicit in the hand-wringing over the death of news organizations (one guest on last week’s Hobson & Holtz Report podcast wondered if PR professionals should even bother tracking newspaper coverage any more) is the concern that good journalism will vanish from the Earth. We’ve always argued that the problem with newspapers today isn’t that they have no value, it’s that they no longer have a sustainable business model. The need for good journalism hasn’t changed but good journalism needs to find new ways to support itself.

Check out two new resources in this area. Jeff Jarvis articulates a future for journalists in an exceptionally cogent summary of his recent work with the City University of New York’s New Business Models for News project. Jarvis sees tomorrow’s journalists as entrepreneurs who create business models around selling their services to those who will pay for them.

We like the analogy to people who work on Hollywood movies. Studios don’t employ legions of camera operators and set designers. They hire that talent as needed for a project. Everyone comes together and works for a few months and then the team breaks up and goes on to other things. Lots of people make their livings that way. Some of them do very well. That’s the way things work in a competitive, entrepreneurial environment.

We like the analogy to people who work on Hollywood movies. Studios don’t employ legions of camera operators and set designers. They hire that talent as needed for a project. Everyone comes together and works for a few months and then the team breaks up and goes on to other things. Lots of people make their livings that way. Some of them do very well. That’s the way things work in a competitive, entrepreneurial environment.

The skills that journalists will need to survive in this decentralized market are very different from the skills they need today. For one thing, young journalists won’t be expected to spend a decade toiling away for pocket change while learning at the knee of some cranky city editor. They’ll be able to make a good living much faster if they have the smarts and skills to compete.

Political skills won’t matter for much because most journalists won’t work for big organizations. Journalists will succeed or fail based upon the quality of their work and their ability to sustain mutually beneficial relationships with multiple employers. Social skills will matter more than political ones. Self-promotion will be essential. There’ll be less time spent in pointless meetings and bitching about the boss at the local bar because, well, there is no boss any more. Journalists will reclaim vast amounts of time that are now spent on organizational bullshit. They’ll spend their time making money instead of covering their asses.

Risky Business

This future is going to look scary to some people because there’s no job security or benefits. But who’s got job security anywhere these days? And benefits plans are being hacked to pieces as businesses downsize. In the future, working for an organization isn’t going to have many advantages over independence. There will still be company jobs for those who prefer them, but a lot of energetic and resourceful journalists will find that life is better on the outside. It’s amazing how productive you can be when you discard all the overhead of working in a big organization. Trust us on that. We left corporate life four years ago and have managed to produce three books and maintain two active blogs while still making a decent living.

Most journalists we’ve talked to are fine with this idea except for one thing: The thought of selling advertising terrorizes them. They have reason to be nervous. Most journalists we know would be lousy salesman (we tried it for a year and hated every minute) so it’s likely that business models will emerge to manage the business details for them. We told you about one of them – GrowthSpur – back in August, and there no doubt will be many others. As news organizations collapse and journalism opportunities disperse out to a million topical blogs and hyperlocal foundries, new ventures will spring up that aggregate opportunities and provide a variety of other services ranging from promotion to ad sales to accounting.

Read Jarvis’ essay for an optimistic perspective on the future opportunities for journalists. No one is suggesting this transition will be easy, but it will result in a market that is vastly more efficient than the one we have known. Journalism schools today should be training their students in the skills of small business management. Those that continue to preach the virtues of working one’s way up through a newsroom hierarchy are doing their students a disservice. Perhaps J-schools will evolve to become subspecialties of colleges of business. That wouldn’t be a bad thing; just different.

Thriving in the Free Economy

To hear some new ideas about how organizations can profit from the emerging free economy, listen to this Churchill Club podcast titled The Free Economy: How Companies Make Money From Giving Things Away. The panel was moderated by Chris Anderson (left), whose new book, Free: The Future of a Radical Price, paints a picture of economic change brought about by the availability of cheap digital distribution. Anderson hosts a panel of entrepreneurs who are making money with businesses that give away all or part of their services for nothing.

To hear some new ideas about how organizations can profit from the emerging free economy, listen to this Churchill Club podcast titled The Free Economy: How Companies Make Money From Giving Things Away. The panel was moderated by Chris Anderson (left), whose new book, Free: The Future of a Radical Price, paints a picture of economic change brought about by the availability of cheap digital distribution. Anderson hosts a panel of entrepreneurs who are making money with businesses that give away all or part of their services for nothing.

We’ve already seen some industries begin to adapt to this new model, but the panel explores some of its finer points, including the popular “fremium” services that offer a bare-bones product to anyone and charge various prices for more powerful features.

A couple of things struck us about the proceedings. One is that pricing can be dependent upon the experience the customer demands. One speaker cites the example of a rock band that gives away its music online but charge for merchandise, concert tickets and command performances. The band has even sold an opportunity to spend the weekend backstage with the group at a price of $75,000. The point is that technology can increasingly customize price to product. This requires a change in thinking for media companies, which have been accustomed to charging the same (usually low) price to everyone and making the money with advertising. In a free economy, more creativity is needed.

Another important point is that businesses can succeed even if only a very small percentage of the customers pay anything. Some panelists are doing quite well with payup rates of as little as 1%. Anderson suggests that a business could be a hit in the future with just a 10% subscription rate.

The key take-away for us was that publishers will need to be more innovative in packaging and pricing their products in the new economy. This creates another differentiation point. Even a company in a commodity business may be able to separate itself from the pack by designing unique bundles and delivery techniques. Conventional wisdom is that delivery is a differentiator, but this discussion suggests otherwise.

Other posts in this series:

The Future of Journalism, Part I